Worth Its Weight in Gold: New Book Examines History of the NWA World Title Belt

By Scott Bowden, Kentucky Fried Rasslin'

July 22nd, 2009

Edited Excerpts for Archival Purposes Only.

Now...we go to school: The Ten Pounds of Gold has everything you

always wanted to know about the NWA belt...but were too much of a mark

to ask.

THE ACE OF BELTS

On Saturday, August 15, 1982, teenaged wrestling fan Dave Millican was watching the 90-minute live Memphis wrestling show when NWA World champion Ric Flair appeared, unannounced in advance, alongside Lance Russell in the WMC-TV studio. Wearing sunglasses, a perfectly pressed double-breasted, navy-blue blazer and white button-down and khakis, Flair almost appeared as if he had steered his yacht down the Mississippi River to arrive in Memphis. In Flair’s hands, the famous “10 pounds of gold”—the championship belt of the National Wrestling Alliance.

Millican had originally seen photos of the belt in the Stanley Weston newsstand publications (a.k.a., “the Apter mags”) years ago, and it had been love at first sight. Sure, Nick Bockwinkel, the AWA World champ, played the role so well that most Memphis fans believed him to be the champion, but Apter-reading marks like Millican and me knew that the NWA strap was considered the big one by the wrestling press. Most important, we had seen Flair all over Mid-Atlantic and World Class TV stylin’ and profilin’ and turning back challenge after challenge against the biggest names in the sport. We knew Flair was the real World heavyweight champion.

“Even at a young age, I appreciated the prestige of the NWA World title,” recalls Millican. “From the syndicated shows, I could see that Flair was making the rounds as World champion—he wasn’t just the champion of a single territory. By the time Flair had made it to Memphis, I had been in enough scrapes and scuffles to know that wrestling wasn’t on the up and up, but the wrestlers in those days made it much easier to suspend disbelief. I was watching Flair and Jerry Lawler go at it, and I remember thinking, ‘This is a studio match and it probably won’t happen—but, man, it would be cool to see Lawler get his hands on that NWA belt.’”

“I had already been making cardboard belt when I was a kid—a cardboard box wasn’t safe around me growing up,” he says. “The first one I made was in the style of what we in the business call the old ‘Levy-style’ belt, with the red, white and blue, similar to the old National title [Georgia territory, circa 1983] and our area’s AWA Southern tag belts [1980-81]. The first belt that really caught my eye was the AWA Southern title that was introduced in Memphis in 1981, with the oval chrome-ring side plates that I’m so fond of. My first memory of the NWA World title was when Terry Funk came to Memphis to defend the title and seeing how excited my older brother and his friends were. And Lance Russell had always done such a good job getting over the importance of Nick Bockwinkel’s AWA title that I also held that belt in high regard. I probably tried my best to copy those two World title belts.”

Also known as the “domed globe” because of the dented globe affixed to the gold buckle, the strap was retired after about 16 years of service to make way for the Big Gold championship belt, which Jim Crockett Jr. purchased for titleholder Ric Flair in 1986. As the final holder of the original 10 pounds of gold from the territory days, Flair kept the championship belt, storing it in a custom-made case for display at the Queen’s Gallery in Charlotte.

Since that time, Millican has become one of the best-known belt-makers in the wrestling business, with his clients including his childhood hero Lawler as well as TNA and UFC. Countless fellow belt marks have secured Dave’s services, often purchasing several high-quality, ring-worthy replicas of NWA, AWA and WWF belts, many of which were originally made by the “King of Belts,” Reggie Parks.

In fact, it was Parks who gave Millican his big break in the belt business. In his late teens, Dave had graduated from cardboard construction of his belts, with help from an uncle who had access to huge sheets of steel at work. Millican began making belts made of stainless steel and trophy metal for wrestlers on the outlaw circuit—small, local promotions not affiliated with wrestling’s major organizations, which often ran in towns where an established promotion like’s Jarrett’s Memphis group was already operating. Most of the outlaw guys either had no belts or ones that resembled Millican’s early work on cardboard, so they greatly appreciated Dave’s advancing handiwork.

Millican was aware that Parks was the belt-maker to the stars; however, because wrestling’s inside information was more closely guarded in the days before the Internet, he had no way of contacting him. An outlaw wrestler showed up one night with a belt in a black velvet bag, a trademark of Parks. Dave got Parks’ number from the guy and contacted him to order a replica of the AWA World title belt worn by Curt Hennig and Lawler. Nervously, he mentioned to Parks that he also made belts, which piqued Reggie’s curiosity. He sent pictures of his work to Parks, who admitted the young man had potential but asked him, “Why don’t you make belts like I make ‘em?” Millican answered, “I’d love to, sir, but I don’t know how.”

Parks took Dave under his winged eagle (a little belt humor there), offering to make the plates for a belt once Millican had his next order, so he could he evaluate his new apprentice’s leather work with real plates.

While Reggie is usually lighthearted and easygoing, he sternly asked Millican, “You wouldn’t put the Mona Lisa in a shitty frame, would you, son? If I see these plates on a shitty-looking strap, then maybe you’ll go back to doing them the way you used to do them. Because if I don’t like what I see, I’ll cut you loose. Deal?”

After Millican agreed to those terms, Lawler let him releather the USWA tag belts that the King and Bill Dundee held at the time. Just one problem: “As soon as I got those belts from Lawler, I went over to Tandy Leather in Memphis, and they didn’t have any good tooling hides in the store—which is kinda like KFC running out of chicken. They only had this really, really thick leather that I had to beat the crap out of to get any kind of impressions. But when I put them in Bill and Jerry’s hands, they loved them. And I breathed a big sigh of relief. I mean, I was thrilled just to be around Bill and Jerry, but you don’t want to come off like the mark that you are when you start off in the business. Everyone knows you’re a mark but you can’t act like it—just one of those weird dynamics of the business.”

Under Parks’ watchful eye, Millican honed his craft until his work was on par with the master belt-maker. Now known as the “Ace of Belts,” Millican is grateful for his break in the business.

“I once asked Reggie, ‘Why me?’ He said that he knew he couldn’t do this forever, so he wanted to make sure someone picked up the slack and made belts the right way after he was gone.”

THE MID-ATLANTIC GATEWAY

Much like Millican years later, Dick Bourne, who helps run the Mid-Atlantic Gateway site, became enamored of the NWA World title following a 1975 angle on Jim Crockett Promotions TV that was similar to the Flair/Lawler scenario in Memphis.

“Jack Brisco wrestled on Mid-Atlantic Wrestling television in 1975 in a non-title match against Wahoo McDaniel,” Bourne says. “Wahoo pinned him to set up title matches around the territory. The title was treated with the utmost importance from the moment I saw Jack Brisco with it on television, and Bob Caudle and Ed Capral, our main announcers then, put it over big each week on TV. It was always special when the champion was in to defend the title. The NWA champions then–Brisco, Funk, Race–always made it clear how much they wanted to keep the title, and our guys made it clear how much they wanted to win it.”

Of course, Bourne and fans throughout the Carolinas were pleased when the local boy—the Nature Boy, Ric Flair that is—captured the belt from Dusty Rhodes in Kansas City in 1981.

“The belt had been defended in our area for eight years before Flair got it,” he says. “Flair holding the title certainly had special meaning to Mid-Atlantic Wrestling fans. We were glad to see our guy get the sport’s top prize.”

Through Michael Boccichio at the highspots.com Web site, Bourne was able to arrange a deal with Flair to photograph the 10 pounds of gold on October 28, 2008, at the Queen’s Gallery. Along with Millican, Bourne took approximately 400 shots of the belt, including pictures of the championship with the blue-and-silver robe worn by Flair when he won the title for the second time at Starrcade ’83.

Millican also brought items from his personal collection of wrestling belts and memorabilia to shoot with the NWA title: the Parks-made U.S. title belt (a.k.a., sometimes referred to as “the 10 pounds of silver”) worn by champions like Magnum T.A. and Tully Blanchard in JCP in the early ’80s, and Kerry Von Erich’s actual ring jacket emblazoned with the words “In Memory of David,” which he wore the day he defeated Flair for the championship in front of 32,000 fans at Texas Stadium on May 6, 1984. In all, Bourne and Millican spent about five hours with the one belt that arguably best represents a bygone era in professional wrestling.

“It’s not a stretch to say that about two of those hours were spent with just Dave and I sitting there talking about it,” Bourne says. “When you hold the belt and think of the guys who held it—and all the guys who stood across the ring challenging for it, and all the places it was defended and the miles it traveled—it’s just a special feeling. It would be no different to me than if we were sitting there holding the Lombardi Trophy or the Stanley Cup – that belt is that special.”

Millican agrees, saying that he can feel the history of the NWA belt any time he’s even near it.

“I’ve spent a fortune collecting as many historical belts as I can get my hands on,” says the Ace, who also owns the ring-used NWA Southern title (Florida) and the ’80s-era World Class tag belt. “I’m in the business because I’m the ultimate belt mark. To get to hold that NWA World title belt—it might sound corny, but…it’s a different experience than any other belt I’ve ever held in my hands.”

Bourne says he was planning to produce a photo book documenting their visit for their own personal use, but then decided to self-publish it as Ten Pounds of Gold: A Close Look at the NWA World Championship Belt.

“With Dave’s knowledge about the history and construction of the belt, it suddenly dawned on me that with the unique photos we had taken and the insights we could put together, it might make an interesting book, for belt aficionados at least, and, hopefully, for fans in general."

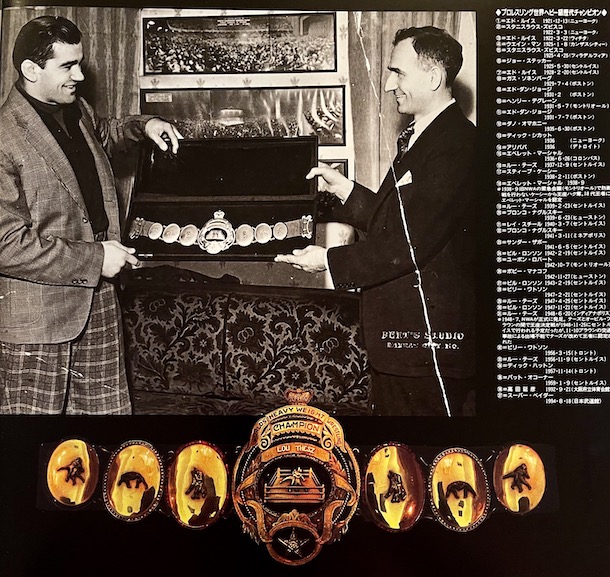

The end result is a gorgeous 80-page historical record of wrestling’s greatest title belt, complete with photos provided by eight-time NWA titlist Race and his wife BJ that show the champ receiving the new gold belt from NWA president Sam Muchnick on July 20, 1973, in Houston. Race, of course, went on to drop his new trophy to challenger Brisco that same night. Also included are brief profiles of the eight men who wore the championship: Race, Brisco, Shohei “Giant” Baba, Funk, Dusty Rhodes, Tommy Rich, Flair and Von Erich. (Nope, no profile of Jack Veneno.)

Most fascinating are the details of the belt’s construction and subtle changes over the years. For example, the wide-cut leather strap on the belt was originally encased in red velvet. For years, I was under the impression that Race had been presented with a black-leather strap that night in Houston, as most of the photos I’d seen were in black-and-white. About seven years ago, I saw color pictures of Brisco defending the title against Baba in Japan and was surprised to see the red belt. While the red velvet looked nice and rather regal, it wasn’t durable for the long haul and sweat stains began to tarnish its appearance. Brisco had the belt re-leathered with a brand-new black-leather strap, with a tighter cut around the buckle—which, in my opinion, enhanced the appearance of the NWA belt. Another interesting tidbit is that shortly after winning the belt, Brisco was honored with a nameplate under the word “WRESTLING” on the buckle, similar to the nameplate on the Big Gold strap made famous by Flair years later. The first nameplate read “Jack Brisco,” while the second version simply read “BRISCO” in all caps. When Funk won the title, the intended “tradition” was disregarded. Even Race was unaware of this aspect of the belt’s history.

In the book, Millican also explains how the belt’s “domed globe,” from which the strap gets that common nickname, was replaced at some point in 1976 during Funk’s reign. The NWA letters were mounted straight across on the first version and arched downward on the replacement globe. Although the first globe was dented and the paint on the black front panels had begun to chip during Brisco’s reign, the belt’s appearance really took a turn for the worse midway through the Funk era as NWA kingpin. At that point, the black panels had completely chipped away (though Millican suspects Funk did this himself as opposed to carrying around a belt with partial panels) and the belt was eventually restored with a new globe (which ended up with a significant dent by the time Rich won the belt on April 27, 1981) and new black onyx panels that were a huge upgrade over the black paint used previously.

“They should have made those panels with onyx to begin with, because it was not only durable but shinier and almost looked like glass in the lights,” Millican says.

The book also reveals what is known about the Mexican jeweler who made the belt, what aspects of its construction surprised him, who he believes coined the term “10 pounds of gold” (the belt actually weighs about 7 pounds) and why the previous belt held by champions like Dory Funk Jr. and Gene Kiniski was replaced to begin with.

The book’s close-up photos are beautiful, revealing minute details, including a clear look at the initials “KVE,” which apparently Kerry scratched onto the buckle before dropping the belt back to Flair in Japan. I was also amused to find that the depiction of the grappling scene to the right of “WRESTLING” on the buckle includes a heavyset wrestler who looks amazingly like Dusty Rhodes. (Millican agrees with me, but Bourne apparently doesn’t see the resemblance.)

All in all, Ten Pounds of Gold: A Close Look at the NWA World Championship Belt is a true labor of love that old-school fans will find fascinating. Pick it up today by clicking here.

*****

Scott Bowden's Kentucky Fried Rasslin'

Scott Bowden Passes Away at age 48 (2020) (f4wonline.com)